Mangyan Indigenous Cultural Communities

"Indigenous peoples have the right to practise and revitalize their cultural traditions and customs.

This includes the right to maintain, protect and develop the past, present and future manifestations

of their cultures, such as archaeological and historical sites, artefacts, designs, ceremonies, technologies and visual and performing arts and literature."

Article 11, UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

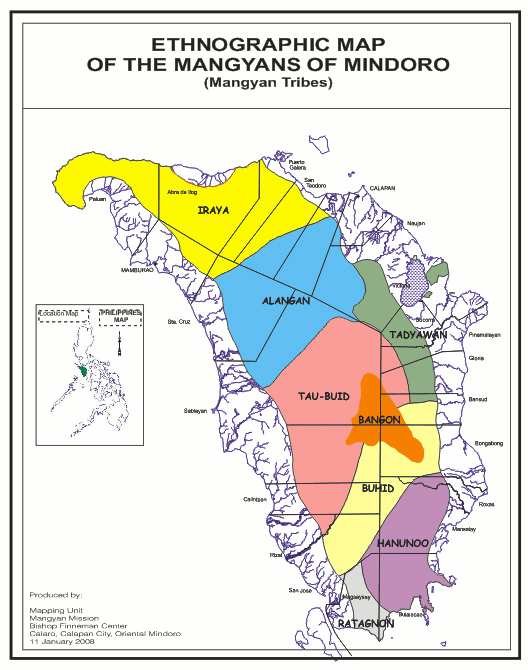

Iraya Mangyans

Estel (1952) described the Iraya as having curly or deep wavy hair and dark skin but not as dark as that of the Negrito.

During ancient times, the Iraya traditional attire was made of dry tree bark, pounded to make it flat and soft. The women usually wore a blouse and a skirt and the men wore g-strings made of cloth. Today, however, the Iraya are dressed just like the lowland people. Ready-to-wear clothes are easier to find than their traditional costume (Uyan, 2002).

The Irayas are also skilled in nito-weaving (forest vines). Handicrafts such as jars, trays, plates and cups of different sizes and designs are being marketed to the lowlanders.

They subsist on rice, banana, sweet potato, and other root crops.

Iraya Mangyan students

Alangan Mangyans

The name Alangan was derived from the name of a river and mountain slopes in the upper Alangan Valley (Leykamm, 1979).

The women traditionally wear a skirt called lingeb, which is made of long strips of woven nito (forest vines), and is wound around the abdomen. Lingeb is worn together with the g-string called abayen. The upper covering is called ulango, made from the leaf of the wild buri palm. Sometimes a red kerchief called limbutong is worn over the ulango. On the other hand, the men wear g-strings with fringes in front.

The Alangan Mangyans practise swidden farming, which consists of eleven stages. Two of them are the firebreak-making (agait) and the fallowing (agpagamas). A firebreak is made so the fire will not go beyond the swidden site where the vegetation is thoroughly dry and ready for burning. Two years after clearing, cultivation of the swidden is normally ceased and the site is allowed to revert back to forest (Quiaoit, 1997).

Betel nut chewing is also noted among the Alangans, like all other Mangyan indigenous groups. This they chew with great fervor from morning to night, saying that they don't feel hunger as long as they chew betel nut (Leykamm, 1979). Nonetheless, betel chewing has a social dimension. Exchange of betel chew ingredients signifies social acceptance.

Tadyawan Mangyans

In the past, the men wore g-strings called abay while the women wore for their upper covering a red cloth called paypay, which is wound around the breast. For their lower covering, they wrapped around the waist a white cloth called talapi. For their accessories, women wore colorful bracelets and necklaces made of beads.

Today the women are rarely seen wearing their traditional attire, though some men still wear the abay.

Like all other Mangyan indigenous groups, the Tadyawan depend on their swidden farm for subsistence. Their staple foods are upland rice, banana, sweet potato, and taro. Some have also planted fruit-bearing trees like rambutan, citrus, and coffee in their swidden farm.

Bangon Mangyans

The Bangon Mangyans have their own culture and language different from the other indigenous groups.

They asserted to be considered the eight major indigenous group instead of a sub-group of the Tau-buid. In a March 28, 1996 meeting with Buhid Mangyans in Ogom Liguma, they decided to accept the word Bangon for their indigenous group.

Tau-buid Mangyans

The Tau-buids are known as pipe smokers.

Standard dress for men and women is the loin cloth. In some areas close to the lowlands, women wrap a knee-length cloth around their bark bra-string and men wear cloth instead of bark. Bark cloth is worn by both men and women in the interior and is also used for head bands, women's breast covers and blankets. Cloth is made by extracting, pounding and drying the inner bark of several trees (Pennoyer, 1979).

Buhid Mangyans

The Buhids are known as pot makers. Other Mangyan tribes, like the Alangan and Hanunuo, used to buy their cooking pots from the Buhids. The word Buhid literally means "mountain dwellers" (Postma, 1967).

Buhid women wear woven black and white brassiers called linagmon and a black and white skirt called abol. Unmarried women wear body ornaments such as a braided nito belt (lufas), blue thread earrings, beaded headband (sangbaw), beaded bracelet (uksong), and beaded long necklace (siwayang or ugot). The men, on the other hand, wear g-strings. To enhance body beauty, the men wear ornaments like a long beaded necklace, tight choker (ugot) and beaded bracelet (uksong). Both sexes use an accessory bag called bay-ong for personal things like comb and knife (Litis, 1989).

Together with the Hanunuo, the Buhids in some areas possess a pre-Spanish syllabic writing system.

.

Hanunuo Mangyans

To the Hanunuo, clothing (rutay) is one of the most important criteria in distinguishing the Mangyan from the non-Mangyan (damuong). A Hanunuo-Mangyan male wears a loin cloth (ba-ag) and a shirt (balukas). A female wears an indigo-dyed short skirt (ramit) and a blouse (lambung). Many of the traditional style shirts and blouses are embroidered on the back with a design called pakudos, based on the cross shape.

This design is also found on their bags made of buri (palm leaf) and nito (forest vine), called bay-ong. Both sexes used to wear a twilled rattan belt with pocket (hagkos) at their waist. Long hair is the traditional style for a man. It is tied in one spot at the back of the head with a cloth hair-band called panyo. Women also have long hair often dressed with a headbands of beads. The Hanunuo Mangyans of all ages and both sexes are very fond of wearing necklaces and bracelets of beads (Miyamoto, 1985).

In the past, they cultivated cotton trees and from these obtained raw materials, which they wove in a crude hand loom called harablon. The process of weaving was called habilan, which starts with the gathering of cotton balls and pilling them to dry in a flat basket (bilao). Afterwards, the seeds are removed and the cotton placed on a mat and beaten by two flat sticks to make it fine. Next, the cotton is placed inside a container made out of banana stalks (binuyo) and woven.

Noted anthropologist Harold Conklin made an extensive study on Hanunuo-Mangyan agricultural system in 1953. The Hanunuo Mangyans practise swidden farming. This type of farming is different from the kaingin system practised by non-Mangyans, which is often very destructive when it is done with no proper safeguards to prevent the fire from spreading to the surrounding vegetation. A fallow period is also observed so that the swidden farm will revert back to forest. According to Conklin, the Mangyans managed their swidden farms skillfully. In 1995, almost half a century after Conklin's research, a study on the Hanunuo Mangyans' swidden farming system was conducted by Hayama Atsuko. She concluded that the Hanunuo Mangyans' farming practices have prevented land deterioration in spite of the fact that forest land degradation is now evident in their territory due to various factors.

Together with their northern neighbor the Buhid Mangyanss, the Hanunuo possess a pre-Spanish writing system, considered to be of Indic origin, with characters expressing the open syllables of the language (Postma, 1981). This syllabic writing system, called Surat Mangyan, is being taught in several Mangyan schools in Mansalay and Bulalacao.

Ratagnon Mangyans

The Ratagnon women wear a wrap-around cotton cloth from the waistline to the knees and some of the males still wear the traditional g-string. The women's breast covering is made of woven nito (forest vine). They also wear accessories made of beads and copper wire.

The males wear a jacket with simple embroidery during gala festivities and carry flint, tinder, and other paraphernalia for making fire. Both sexes wear coils of red-dyed rattan at the waistline. Like other Mangyan tribes, they also carry betel chew and its ingredients in bamboo containers.